Fossile et psyché

Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc

08.11.2018 - 26.01.2019, vernissage 08.11.2018

[plus bas en français]

Knowledge, with Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, is not far from being a performance of dream. Each time he gets closer to materials and to their complex operations, one can’t help but think that he also gets closer to dream. This learning of dream, which the artist uses on a daily basis in order to evolve, involves asserting parallel lives, of which we know at least two striking sides: the life of the researcher, always seeking to bring together his family of thinkers and artists, and that of the explorer, using his body to gain access to his own memory, partially buried in the ground of the Guyanese forest.

CB: Mathieu’s relationship to time is more indomitable than chronological, working on ways of opening to what is different, like the forest or the Savanna, perceived as living and unpredictable creatures in the work of the poet and writer Wilson Harris, who came from the same region (the Guiana Shield) as him. The writer’s intense and highly metaphorical vision accompanies the artist even in the production processes of his recent works. The ongoing exhibition at the Rochechouart museum is a very beautiful invitation to travel. Each piece shows an unstable and even suspicious image of nature, capable of diverting, like in the waterland of Guyana. The exhibition is the place where dreams remain accessible, within reach. The works discover themselves, like us, in a state of constant evolution, they fluidify this access to the unconscious, and make palpable the common denominator that links us all to landscapes: whether they conceal or reveal their secrets, one has to fight against the possibility of a sudden reversal (the moment when the positive ceases to be, when it slides into the negative, and vice versa). Any precious material, originating from the bowels of the earth, is riddled with beliefs and destruction — this is what is whispered by these red, pulsating and peaceful paintings, which reveal through their legend (Study for the ransom room (Atahualpa), cinnabar on copper, 2018) their poisonous and uncontrollable nature.

IA: I’m returning to Wilson Harris and to his text « Fossil and Psyche », in which he underlines the modern ability to distance ourselves from the past lack of freedom and to delude ourselves about the freedom offered by the present: he analyses several literary works which address expeditions as exploitation narratives. You were talking about landscape and buried memory: no landscape we explore is actually new according to Harris, it brings us back to a mental landscape — the location of the « authentic discovery »* of our past, of our own alienation, of what continues to be a burden to us over generations. This impetus towards the Guyanese landscape is less of a return to origins for Mathieu, than a path that he regularly takes. The other day you evoked his older, « found footage » pieces, like The Edge of the world (2003). The forest was already there. The exploration was mental before being implemented through several return trips undertaken by the artist along the Maroni River, looking for Wacapou, a gold miners village that has disappeared, and where the house of his mother used to be. His previous exhibition at the gallery, Chimen Chyen (2015), recounted one of his first trips, which had resulted in the failure to find the house, and in the accidental, partial destruction of the Super 8 footage he had brought back. Fossil and Psyche reveals Mathieu’s deeper penetration into the forest, which now covers the old village of Wacapou. The objets bearing witness to the location of the village — which were found thanks to a local guide — and the materials he uses as substitutes for the mercury polluting the shores of the Maroni river (cinnabar brushed over copper frames, turtle shells coated with gallium) are signs, within the exhibition, of the partial domesticating of the landscape. Like the ability acquired over time to appropriate his own past and to engage more directly with what shapes our unconscious.

CB: In fact, I believe that Mathieu increasingly considers his productions as parts of this living creature that the landscape constitutes. All his recent works expand his view of reality as physical and even carnal, through which materiality embraces and bites like in the work of the filmmaker Ciro Guerra (Embrace of the Serpent, 2015). The work keeps experiencing, throughout its life, a slow mutation, which is also that of humanity — there is necessarily a form of entanglement, contamination and even symbiosis. The great variety of materials used at Rochechouart, like at the gallery, does not contradict Mathieu’s desire to trigger events that can be connected through the principles of communicating vessels — that is a fluid mechanics in which the content is in equilibrium regardless of the volume and the shape of the container. The forms of the exhibition are like this, they only dream of letting something escape (a breath, music or toxic compounds that are natural or chemical), like one frees speech, knowing that a word can « set us in motion ». It can lead us very far away, if one refers again to Wilson Harris: towards the reconstruction of the « I », as well as towards the Other, and towards a certain form of completeness, which involves the understanding of powerful rhythms before finding one’s own. Living exposed to the risk of the landscape, like to the risk of others. Addressing death as outstanding collective work or the exhibition as the form of reconciliation. I will end with this quote that a friend recently sent me: « Perhaps, like the war survivors themselves, we need to tell and tell until all our stories of death and near-death and gratuitous life are standing with us to face the challenges of the present.»**

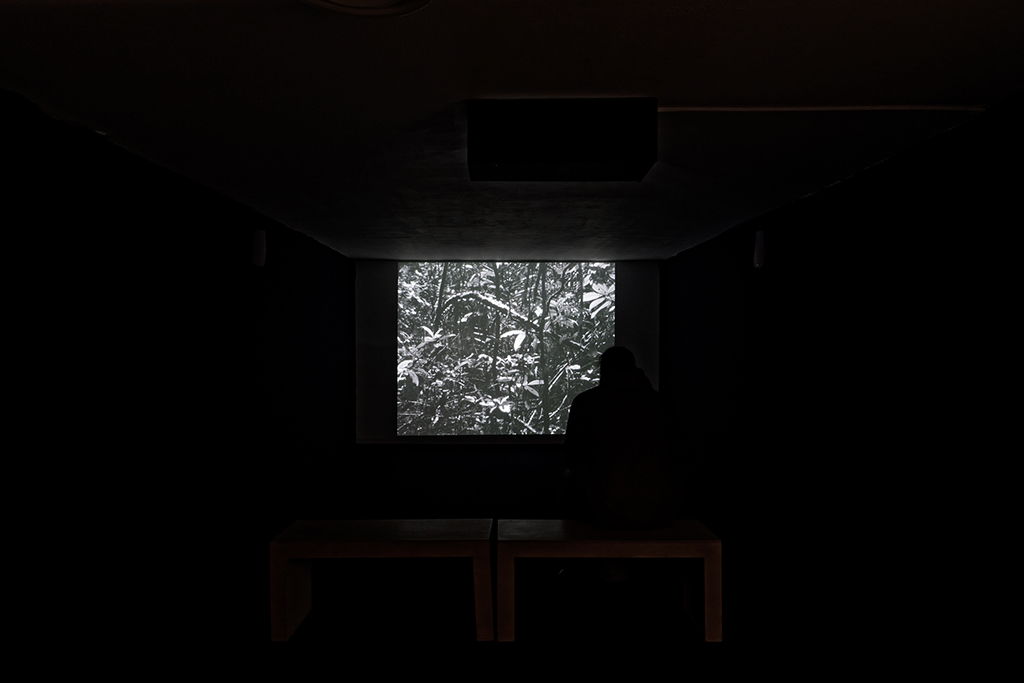

IA: the exhibitions taking place at the gallery and at the Rochechouart Museum end with the screening of Wacapou, prologue or A room in my mother’s house, a film that partly echoes the narrative undertaking developed in Secteur IX B (2015), the artist’s previous film. The heroine of the latter suffers from hallucinations due to the ingestion of drugs from the « colonial first aid kit » and seems contaminated by her subject of research, the Dakar-Djibouti expedition evoked by Michel Leiris in Phantom Africa. By changing the continent and getting closer to his personal history, Mathieu returns to a production method that is more simple, editing archive images borrowed from the anthropologist Michèle Baj-Strobel and from his mother, and footage shot with Victor Zébo on the Maroni river and then in the forest covering Wacapou in December 2017. The music composed by Thomas Tilly as well as Mary-Jane Leach supports this form which, although it is more abstract, underscores the same possibility of getting contaminated, or even profoundly affected down to our unconscious by what we observe or search. The archive-landscape, considered as the memory of past events, enables one to relive trauma, as opposed to studying it from afar. I believe that we both share the idea of an alchemical transformation from historical memory to the work of art.

*Wilson Harris, Fossil and psyche, Occasional publication, African and Afro-American Studies and Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin, 1974, p.9

**Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton University Press, 2017. p.34

traduction: Callisto McNulty

Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc was born in 1977, he lives in Sète (France). In recent years, he has exhibited his work at the Jumex Foundation, at the Kunstforum Baloise (2018), at the MMK Frankfurt (2016), at the Kunsthalle Basel, at the Bielefelder Kunstverein (2013) or at the Serralves Foundation, Porto (2012). He participated in the 56th Venice Biennale (the international exhibition and the Belgian Pavilion, 2015), the 8th Berlin Biennale (2014), La Triennale, Paris (2012) and Manifesta 8 (2010). He received the Baloise Art Prize (2015) awarded in the context of Art Basel.

Fossile and Psyche is organised in parallel to the exhibition Palace of the peacock at The Rochechouart Departmental Museum of Contemporary Art (until December 16, 2018).

--

Le savoir chez Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc n’est pas loin d’être une performance du rêvé. Chaque fois qu’il est au plus près de la matière et de ses opérations complexes, on ne peut s’empêcher de penser qu’il est aussi au plus près du rêve. Cet apprentissage du rêve dont l’artiste se sert au quotidien pour évoluer passe par l’affirmation de vies parallèles, dont nous connaissons au moins deux versants marquants : la vie du chercheur, toujours prêt à réunir sa famille de penseur·euse·s et d’artistes, et celle de l’explorateur, utilisant son corps pour accéder à sa propre mémoire, partiellement enfouie dans le sol de la forêt guyanaise.

CB : Mathieu entretient un rapport au temps plus indomptable que chronologique, travaillant des manières de s’ouvrir à ce qui est différent, à l’image de la forêt ou de la Savane, perçues comme créatures vivantes et imprévisibles dans l’œuvre du poète et écrivain Wilson Harris, originaire de la même région (le plateau des Guyanes) que lui. La vision intense et très imagée de l’écrivain accompagne l’artiste jusque dans les processus de fabrication de ses œuvres récentes. L’exposition encore en cours au musée de Rochechouart est une très belle invitation au voyage. Chaque œuvre montre une nature instable et louche, capable de bifurquer, comme au pays des eaux qu’est la Guyane. L’exposition est l’endroit où les rêves restent accessibles, à portée de main. Les œuvres se découvrent comme nous en constante évolution, elles fluidifient cet accès à l’inconscient et rendent palpable ce dénominateur commun qui nous lie tout·e·s aux paysages : qu’ils se taisent ou qu’ils livrent leurs secrets, il faut en découdre avec la possibilité d’un renversement brutal (moment où le positif cesse de l’être, où il glisse vers le négatif, et inversement). Toute matière précieuse née des entrailles de la terre est hérissée de croyances et de destructions, c’est ce que murmurent ces peintures rouges palpitantes et tranquilles qui rapportent par leur légende (Etudes pour la chambre de la rançon (Atahualpa), cinabre sur châssis en cuivre, 2018) leur nature vénéneuse et incontrôlable.

IA : Je reviens sur Wilson Harris et son texte « Fossile et psyché », dans lequel il souligne la capacité moderne à prendre de la distance vis-à-vis d’un manque de liberté passé et à nous illusionner sur la liberté offerte par le présent : il analyse plusieurs œuvres littéraires traitant d’expéditions comme étant en creux, des récits d’exploitation. Tu parlais de paysage et de mémoire enfouie: aucun paysage que nous explorons n’est en réalité nouveau selon Harris, il nous ramène à un paysage mental, lieu de « découverte authentique »* de notre passé, de notre propre aliénation, de ce qui continue à nous encombrer au fil des générations. Cet élan vers le paysage guyanais est moins un retour aux sources pour Mathieu, qu’un chemin de traverse régulièrement emprunté. Tu évoquais l’autre jour ses œuvres anciennes, réalisées en « found footage », comme Le Bord du monde (2003). La forêt était déjà là. L’exploration était mentale avant d’être concrétisée par plusieurs voyages retour que l’artiste a effectués le long du fleuve Maroni à la recherche de Wacapou, village d’orpailleurs disparu où se trouvait la maison de sa mère. Son exposition précédente à la galerie, Chimen Chyen (2015) narrait l’un de ces premiers voyages qui s’était soldé par un échec à trouver la maison, et par la destruction partielle et fortuite des images super 8 qu’il avait ramenées. Fossile et psyché révèle une pénétration plus profonde de Mathieu dans la forêt qui recouvre aujourd’hui l’ancien village de Wacapou. Les objets témoins de l’emplacement du village - trouvés grâce à un guide local - et les matériaux qu’il utilise comme substituts du mercure polluant les rivages du Maroni (cinabre brossé sur des cadres en cuivre, gallium versé dans des carapaces de tortue) sont autant de signes, dans l’exposition, de l’apprivoisement partiel du paysage. Comme une capacité acquise avec le temps de s’approprier son propre passé et de faire face plus directement à ce qui forme notre inconscient.

CB : Je crois que Mathieu voit de plus en plus ses productions comme des parties de cette créature vivante qu’est le paysage. Toutes ses propositions récentes augmentent sa vison d’une réalité physique et même charnelle à travers laquelle la matière étreint et mord comme chez le réalisateur Ciro Guerra (L’étreinte du serpent, 2015). L’œuvre poursuit au fil de sa vie une lente mutation qui est aussi celle de l’humanité, il y a forcément enchevêtrement, contamination et même symbiose. La variété des matériaux utilisés à Rochechouart comme à la galerie ne contredit pas l’envie chez Mathieu de provoquer des évènements qui puissent se relier par des principes de vases communicants, soit une mécanique des fluides par laquelle le contenu s’équilibre indépendamment du volume et de la forme de son contenant. Les formes de l’exposition sont ainsi, elles ne rêvent que de laisser échapper quelque chose (un souffle, une musique ou encore des composés toxiques naturels ou chimiques), comme on libère la parole, sachant que le mot peut nous « mettre en marche ». Il peut conduire très loin si l’on s’en réfère encore à Wilson Harris : à la reconstitution du Moi comme à l’Autre, à une certaine complétude qui passe par la compréhension de rythmes puissants avant de trouver le sien propre. Vivre au risque du paysage comme au risque des autres. Penser la mort comme un travail collectif encore en suspens ou l’exposition en tant que forme de la réconciliation. Je terminerais par cette citation qu’un ami m’a récemment envoyé : « peut-être, comme les survivants de la guerre eux-mêmes, avons-nous besoin de raconter encore et toujours, jusqu'à ce que nos histoires de mises à mort, de frôlements de la mort ou de vies épargnées nous aident à faire face aux défis du présent. »**

IA : les expositions de la galerie et de Rochechouart s’achèvent sur la projection de Wacapou, un prologue ou Une pièce dans la maison de ma mère un film qui rejoint par endroits l’entreprise narrative de Secteur IX B (2015), réalisation précédente de l’artiste. L’héroïne de ce dernier est atteinte d’hallucinations dues à l’ingestion de médicaments provenant de la « boîte à pharmacie coloniale » et semble contaminée par son objet d’étude, l’expédition Dakar-Djibouti évoquée par Michel Leiris dans L’Afrique fantôme. En changeant de continent et se rapprochant de son histoire personnelle, Mathieu revient à une méthode de production plus simple, réalisant un montage d’images d’archives empruntées à l’anthropologue Michèle Baj-Strobel et à sa mère, et de plans tournés avec Victor Zébo sur le fleuve Maroni puis dans la forêt recouvrant Wacapou en décembre 2017. La musique composée par Thomas Tilly mais aussi par Mary-Jane Leach soutient cette forme qui, bien que plus abstraite, souligne la même possibilité de se trouver contaminé·e, voire profondément affecté·e jusqu’à notre inconscient, par ce que nous observons ou cherchons. Le paysage-archive considéré comme mémoire des événements passés permet de revivre le trauma, plus que de l’étudier de façon distanciée. Il me semble que nous partageons toutes deux l’idée d’un passage alchimique de la mémoire historique à l’œuvre d’art.

*Wilson Harris, Fossil and psyche, Ocasional publication, African and Afro-American Studies and Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin, 1974.

**Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Le champignon de la fin du monde - Sur la possibilité de vivre dans les ruines du capitalisme, Les Éditions de la découverte, Paris, 2017, p75.

Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc est né en 1977, il vit à Sète (France). Ces dernières années, il a exposé son travail à la Fondation Jumex, au Kunstforum Bâloise (2018), au MMK Francfort (2016), à la Kunsthalle Basel, au Bielefelder Kunstverein (2013) ou à la Fondation Serralves à Porto (2012). Il a participé à la 56ème Biennale de Venise (exposition internationale et Pavillon belge, 2015), à la 8ème Biennale de Berlin (2014), à la Triennale, Paris (2012) et à Manifesta 8 (2010). Il est lauréat du Prix Bâloise pour l’Art (2015) décerné dans le cadre de la foire Art Basel.

Fossile et Psyché est organisée en parallèle de l’exposition Le Palais du paon au Musée départemental d’Art contemporain de Rochechouart (jusqu’au 16 décembre 2018).